Lab 1: MC Statistical Analysis¶

Topics covered in this lab¶

This lab focuses on the basics of analyzing data from MC calculations. In this lab, participants will use data from VMC calculations of a simple 1-electron system with an analytically soluble system (the ground state of the hydrogen atom) to understand how to interpret an MC situation. Most of these analyses will also carry over to DMC simulations. Topics covered include:

Averaging MC variables

The statisical error bar of mean values

The effects of autocorrelation and variance on the error bar

The relationship between MC time step and autocorrelation

The use of blocking to reduce autocorrelation

The significance of the acceptance ratio

The significance of the sample size

How to determine whether an MC run was successful

The relationship between wavefunction quality and variance

Gauging the efficiency of MC runs

The cost of scaling up to larger system sizes

Lab directories and files¶

labs/lab1_qmc_statistics/

│

├── atom - H atom VMC calculation

│ ├── H.s000.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data

│ └── H.xml - H atom VMC input file

│

├── autocorrelation - varying autocorrelation

│ ├── H.dat - data for gnuplot

│ ├── H.plt - gnuplot for time step vs. E_L, tau_c

│ ├── H.s000.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data: time step = 10

│ ├── H.s001.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data: time step = 5

│ ├── H.s002.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data: time step = 2

│ ├── H.s003.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data: time step = 1

│ ├── H.s004.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data: time step = 0.5

│ ├── H.s005.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data: time step = 0.2

│ ├── H.s006.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data: time step = 0.1

│ ├── H.s007.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data: time step = 0.05

│ ├── H.s008.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data: time step = 0.02

│ ├── H.s009.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data: time step = 0.01

│ ├── H.s010.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data: time step = 0.005

│ ├── H.s011.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data: time step = 0.002

│ ├── H.s012.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data: time step = 0.001

│ ├── H.s013.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data: time step = 0.0005

│ ├── H.s014.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data: time step = 0.0002

│ ├── H.s015.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data: time step = 0.0001

│ └── H.xml - H atom VMC input file

│

├── average - Python scripts for average/std. dev.

│ ├── average.py - average five E_L from H atom VMC

│ ├── stddev2.py - standard deviation using (E_L)^2

│ └── stddev.py - standard deviation around the mean

│

├── basis - varying basis set for orbitals

│ ├── H__exact.s000.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data using STO basis

│ ├── H_STO-2G.s000.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data using STO-2G basis

│ ├── H_STO-3G.s000.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data using STO-3G basis

│ └── H_STO-6G.s000.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data using STO-6G basis

│

├── blocking - varying block/step ratio

│ ├── H.dat - data for gnuplot

│ ├── H.plt - gnuplot for N_block vs. E, tau_c

│ ├── H.s000.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data 50000:1 blocks:steps

│ ├── H.s001.scalar.dat - " " " " 25000:2 blocks:steps

│ ├── H.s002.scalar.dat - " " " " 12500:4 blocks:steps

│ ├── H.s003.scalar.dat - " " " " 6250: 8 blocks:steps

│ ├── H.s004.scalar.dat - " " " " 3125:16 blocks:steps

│ ├── H.s005.scalar.dat - " " " " 2500:20 blocks:steps

│ ├── H.s006.scalar.dat - " " " " 1250:40 blocks:steps

│ ├── H.s007.scalar.dat - " " " " 1000:50 blocks:steps

│ ├── H.s008.scalar.dat - " " " " 500:100 blocks:steps

│ ├── H.s009.scalar.dat - " " " " 250:200 blocks:steps

│ ├── H.s010.scalar.dat - " " " " 125:400 blocks:steps

│ ├── H.s011.scalar.dat - " " " " 100:500 blocks:steps

│ ├── H.s012.scalar.dat - " " " " 50:1000 blocks:steps

│ ├── H.s013.scalar.dat - " " " " 40:1250 blocks:steps

│ ├── H.s014.scalar.dat - " " " " 20:2500 blocks:steps

│ ├── H.s015.scalar.dat - " " " " 10:5000 blocks:steps

│ └── H.xml - H atom VMC input file

│

├── blocks - varying total number of blocks

│ ├── H.dat - data for gnuplot

│ ├── H.plt - gnuplot for N_block vs. E

│ ├── H.s000.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data 500 blocks

│ ├── H.s001.scalar.dat - " " " " 2000 blocks

│ ├── H.s002.scalar.dat - " " " " 8000 blocks

│ ├── H.s003.scalar.dat - " " " " 32000 blocks

│ ├── H.s004.scalar.dat - " " " " 128000 blocks

│ └── H.xml - H atom VMC input file

│

├── dimer - comparing no and simple Jastrow factor

│ ├── H2_STO___no_jastrow.s000.scalar.dat - H dimer VMC data without Jastrow

│ └── H2_STO_with_jastrow.s000.scalar.dat - H dimer VMC data with Jastrow

│

├── docs - documentation

│ ├── Lab_1_MC_Analysis.pdf - this document

│ └── Lab_1_Slides.pdf - slides presented in the lab

│

├── nodes - varying number of computing nodes

│ ├── H.dat - data for gnuplot

│ ├── H.plt - gnuplot for N_node vs. E

│ ├── H.s000.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data with 32 nodes

│ ├── H.s001.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data with 128 nodes

│ └── H.s002.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data with 512 nodes

│

├── problematic - problematic VMC run

│ └── H.s000.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data with a problem

│

└── size - scaling with number of particles

├── 01________H.s000.scalar.dat - H atom VMC data

├── 02_______H2.s000.scalar.dat - H dimer " "

├── 06________C.s000.scalar.dat - C atom " "

├── 10______CH4.s000.scalar.dat - methane " "

├── 12_______C2.s000.scalar.dat - C dimer " "

├── 16_____C2H4.s000.scalar.dat - ethene "

├── 18___CH4CH4.s000.scalar.dat - methane dimer VMC data

├── 32_C2H4C2H4.s000.scalar.dat - ethene dimer " "

├── nelectron_tcpu.dat - data for gnuplot

└── Nelectron_tCPU.plt - gnuplot for N_elec vs. t_CPU

Atomic units¶

QMCPACK operates in Ha atomic units to reduce the number of factors in the Schrödinger equation. Thus, the unit of length is the bohr (5.291772 \(\times 10^{-11}\) m = 0.529177 Å); the unit of energy is the Ha (4.359744 \(\times 10^{-18}\) J = 27.211385 eV). The energy of the ground state of the hydrogen atom in these units is -0.5 Ha.

Reviewing statistics¶

We will practice taking the average (mean) and standard deviation of some MC data by hand to review the basic definitions.

Enter Python’s command line by typing python [Enter]. You will see a

prompt “>>>.”

The mean of a dataset is given by:

To calculate the average of five local energies from an MC calculation

of the ground state of an electron in the hydrogen atom, input (truncate

at the thousandths place if you cannot copy and paste; script versions

are also available in the average directory):

(

(-0.45298911858) +

(-0.45481953564) +

(-0.48066105923) +

(-0.47316713469) +

(-0.46204733302)

)/5.

Then, press [Enter] to get:

>>> ((-0.45298911858) + (-0.45481953564) + (-0.48066105923) +

(-0.47316713469) + (-0.4620473302))/5.

-0.46473683566800006

To understand the significance of the mean, we also need the standard deviation around the mean of the data (also called the error bar), given by:

To calculate the standard deviation around the mean (-0.464736835668) of these five data points, put in:

( (1./(5.*(5.-1.))) * (

(-0.45298911858-(-0.464736835668))**2 + \\

(-0.45481953564-(-0.464736835668))**2 +

(-0.48066105923-(-0.464736835668))**2 +

(-0.47316713469-(-0.464736835668))**2 +

(-0.46204733302-(-0.464736835668))**2 )

)**0.5

Then, press [Enter] to get:

>>> ( (1./(5.*(5.-1.))) * ( (-0.45298911858-(-0.464736835668))**2 +

(-0.45481953564-(-0.464736835668))**2 + (-0.48066105923-(-0.464736835668))**2 +

(-0.47316713469-(-0.464736835668))**2 + (-0.46204733302-(-0.464736835668))**2

) )**0.5

0.0053303187464332066

Thus, we might report this data as having a value -0.465 +/- 0.005 Ha. This calculation of the standard deviation assumes that the average for this data is fixed, but we can continually add MC samples to the data, so it is better to use an estimate of the error bar that does not rely on the overall average. Such an estimate is given by:

To calculate the standard deviation with this formula, input the following, which includes the square of the local energy calculated with each corresponding local energy:

( (1./(5.-1.)) * (

(0.60984565298-(-0.45298911858)**2) + \\

(0.61641291630-(-0.45481953564)**2) +

(1.35860151160-(-0.48066105923)**2) + \\

(0.78720769003-(-0.47316713469)**2) +

(0.56393677687-(-0.46204733302)**2) )

)**0.5

and press [Enter] to get:

>>> ((1./(5.-1.))*((0.60984565298-(-0.45298911858)**2)+

(0.61641291630-(-0.45481953564)**2)+(1.35860151160-(-0.48066105923)**2)+

(0.78720769003-(-0.47316713469)**2)+(0.56393677687-(-0.46204733302)**2))

)**0.5

0.84491636672906634

This much larger standard deviation, acknowledging that the mean of this small data set is not the average in the limit of infinite sampling, more accurately reports the value of the local energy as -0.5 +/- 0.8 Ha.

Type quit() and press [Enter] to exit the Python command line.

Inspecting MC Data¶

QMCPACK outputs data from MC calculations into files ending in

scalar.dat. Several quantities are calculated and written for each

block of MC steps in successive columns to the right of the step index.

Change directories to atom, and open the file ending in

scalar.dat with a text editor (e.g., vi *.scalar.dat or emacs

*.scalar.dat. If possible, adjust the terminal so that lines do not

wrap. The data will begin as follows (broken into three groups to fit on

this page):

# index LocalEnergy LocalEnergy_sq LocalPotential ...

0 -4.5298911858e-01 6.0984565298e-01 -1.1708693521e+00

1 -4.5481953564e-01 6.1641291630e-01 -1.1863425644e+00

2 -4.8066105923e-01 1.3586015116e+00 -1.1766446209e+00

3 -4.7316713469e-01 7.8720769003e-01 -1.1799481122e+00

4 -4.6204733302e-01 5.6393677687e-01 -1.1619244081e+00

5 -4.4313854290e-01 6.0831516179e-01 -1.2064503041e+00

6 -4.5064926960e-01 5.9891422196e-01 -1.1521370176e+00

7 -4.5687452611e-01 5.8139614676e-01 -1.1423627617e+00

8 -4.5018503739e-01 8.4147849706e-01 -1.1842075439e+00

9 -4.3862013841e-01 5.5477715836e-01 -1.2080979177e+00

The first line begins with a #, indicating that this line does not contain MC data but rather the labels of the columns. After a blank line, the remaining lines consist of the MC data. The first column, labeled index, is an integer indicating which block of MC data is on that line. The second column contains the quantity usually of greatest interest from the simulation: the local energy. Since this simulation did not use the exact ground state wavefunction, it does not produce -0.5 Ha as the local energy although the value lies within about 10%. The value of the local energy fluctuates from block to block, and the closer the trial wavefunction is to the ground state the smaller these fluctuations will be. The next column contains an important ingredient in estimating the error in the MC average—the square of the local energy—found by evaluating the square of the Hamiltonian.

... Kinetic Coulomb BlockWeight ...

7.1788023352e-01 -1.1708693521e+00 1.2800000000e+04

7.3152302871e-01 -1.1863425644e+00 1.2800000000e+04

6.9598356165e-01 -1.1766446209e+00 1.2800000000e+04

7.0678097751e-01 -1.1799481122e+00 1.2800000000e+04

6.9987707508e-01 -1.1619244081e+00 1.2800000000e+04

7.6331176120e-01 -1.2064503041e+00 1.2800000000e+04

7.0148774798e-01 -1.1521370176e+00 1.2800000000e+04

6.8548823555e-01 -1.1423627617e+00 1.2800000000e+04

7.3402250655e-01 -1.1842075439e+00 1.2800000000e+04

7.6947777925e-01 -1.2080979177e+00 1.2800000000e+04

The fourth column from the left consists of the values of the local potential energy. In this simulation, it is identical to the Coulomb potential (contained in the sixth column) because the one electron in the simulation has only the potential energy coming from its interaction with the nucleus. In many-electron simulations, the local potential energy contains contributions from the electron-electron Coulomb interactions and the nuclear potential or pseudopotential. The fifth column contains the local kinetic energy value for each MC block, obtained from the Laplacian of the wavefunction. The sixth column shows the local Coulomb interaction energy. The seventh column displays the weight each line of data has in the average (the weights are identical in this simulation).

... BlockCPU AcceptRatio

6.0178991748e-03 9.8515625000e-01

5.8323097461e-03 9.8562500000e-01

5.8213412744e-03 9.8531250000e-01

5.8330412549e-03 9.8828125000e-01

5.8108362256e-03 9.8625000000e-01

5.8254170264e-03 9.8625000000e-01

5.8314813086e-03 9.8679687500e-01

5.8258469971e-03 9.8726562500e-01

5.8158433545e-03 9.8468750000e-01

5.7959401123e-03 9.8539062500e-01

The eighth column shows the CPU time (in seconds) to calculate the data in that line. The ninth column from the left contains the acceptance ratio (1 being full acceptance) for MC steps in that line’s data. Other than the block weight, all quantities vary from line to line.

Exit the text editor ([Esc] :q! [Enter] in vi, [Ctrl]-x [Ctrl]-c in emacs).

Averaging quantities in the MC data¶

QMCPACK includes the qmca Python tool to average quantities in the

scalar.dat file (and also the dmc.dat file of DMC simulations).

Without any flags, qmca will output the average of each column with a

quantity in the scalar.dat file as follows.

Execute qmca by qmca *.scalar.dat, which for this data outputs:

H series 0

LocalEnergy = -0.45446 +/- 0.00057

Variance = 0.529 +/- 0.018

Kinetic = 0.7366 +/- 0.0020

LocalPotential = -1.1910 +/- 0.0016

Coulomb = -1.1910 +/- 0.0016

LocalEnergy_sq = 0.736 +/- 0.018

BlockWeight = 12800.00000000 +/- 0.00000000

BlockCPU = 0.00582002 +/- 0.00000067

AcceptRatio = 0.985508 +/- 0.000048

Efficiency = 0.00000000 +/- 0.00000000

After one blank, qmca prints the title of the subsequent data, gleaned

from the data file name. In this case, H.s000.scalar.dat became “H

series 0.” Everything before the first “.s” will be interpreted as

the title, and the number between “.s” and the next “.” will be

interpreted as the series number.

The first column under the title is the name of each quantity qmca averaged. The column to the right of the equal signs contains the average for the quantity of that line, and the column to the right of the plus-slash-minus is the statistical error bar on the quantity. All quantities calculated from MC simulations have and must be reported with a statistical error bar!

Two new quantities not present in the scalar.dat file are computed

by qmca from the data—variance and efficiency. We will look at these

later in this lab.

To view only one value, qmca takes the -q (quantity) flag. For

example, the output of qmca -q LocalEnergy *.scalar.dat in this

directory produces a single line of output:

H series 0 LocalEnergy = -0.454460 +/- 0.000568

Type qmca –help to see the list of all quantities and their

abbreviations.

Evaluating MC simulation quality¶

There are several aspects of a MC simulation to consider in deciding how well it went. Besides the deviation of the average from an expected value (if there is one), the stability of the simulation in its sampling, the autocorrelation between MC steps, the value of the acceptance ratio (accepted steps over total proposed steps), and the variance in the local energy all indicate the quality of an MC simulation. We will look at these one by one.

Tracing MC quantities¶

Visualizing the evolution of MC quantities over the course of the simulation by a trace offers a quick picture of whether the random walk had the expected behavior. qmca plots traces with the -t flag.

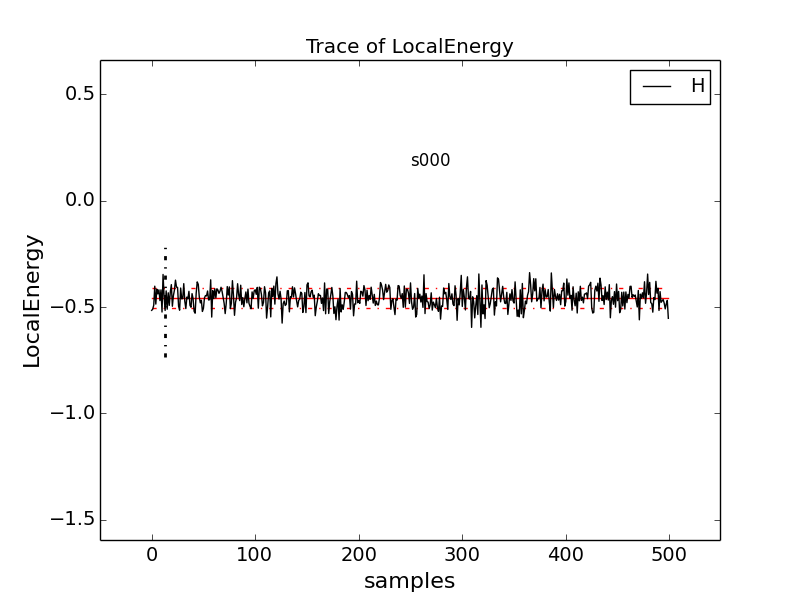

Type qmca -q e -t H.s000.scalar.dat, which produces a graph of the

trace of the local energy:

The solid black line connects the values of the local energy at each MC block (labeled “samples”). The average value is marked with a horizontal, solid red line. One standard deviation above and below the average are marked with horizontal, dashed red lines.

The solid black line connects the values of the local energy at each MC block (labeled “samples”). The average value is marked with a horizontal, solid red line. One standard deviation above and below the average are marked with horizontal, dashed red lines.

The trace of this run is largely centered on the average with no large-scale oscillations or major shifts, indicating a good-quality MC run.

Try tracing the kinetic and potential energies, seeing that their behavior is comparable with the total local energy.

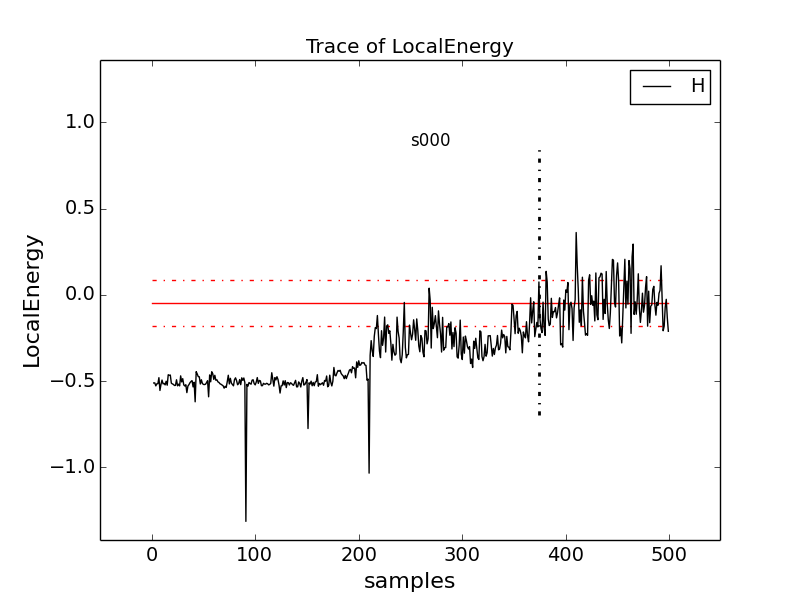

Change to directory problematic and type

qmca -q e -t H.s000.scalar.dat to produce this graph:

Here, the local energy samples cluster around the expected -0.5 Ha for the first 150 samples or so and then begin to oscillate more wildly and increase erratically toward 0, indicating a poor-quality MC run.

Again, trace the kinetic and potential energies in this run and see how their behavior compares with the total local energy.

Blocking away autocorrelation¶

Autocorrelation occurs when a given MC step biases subsequent MC steps, leading to samples that are not statistically independent. We must take this autocorrelation into account to obtain accurate statistics. qmca outputs autocorrelation when given the –sac flag.

Change to directory autocorrelation and type

qmca -q e --sac H.s000.scalar.dat.

H series 0 LocalEnergy = -0.454982 +/- 0.000430 1.0

The value after the error bar on the quantity is the autocorrelation (1.0 in this case).

Proposing too small a step in configuration space, the MC time step,

can lead to autocorrelation since the new samples will be in the

neighborhood of previous samples. Type grep timestep H.xml to see

the varying time step values in this QMCPACK input file (H.xml):

<parameter name="timestep">10</parameter>

<parameter name="timestep">5</parameter>

<parameter name="timestep">2</parameter>

<parameter name="timestep">1</parameter>

<parameter name="timestep">0.5</parameter>

<parameter name="timestep">0.2</parameter>

<parameter name="timestep">0.1</parameter>

<parameter name="timestep">0.05</parameter>

<parameter name="timestep">0.02</parameter>

<parameter name="timestep">0.01</parameter>

<parameter name="timestep">0.005</parameter>

<parameter name="timestep">0.002</parameter>

<parameter name="timestep">0.001</parameter>

<parameter name="timestep">0.0005</parameter>

<parameter name="timestep">0.0002</parameter>

<parameter name="timestep">0.0001</parameter>

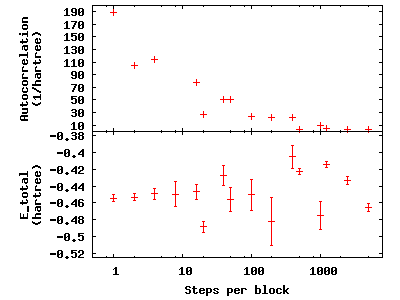

Generally, as the time step decreases, the autocorrelation will increase

(caveat: very large time steps will also have increasing

autocorrelation). To see this, type qmca -q e --sac *.scalar.dat to

see the energies and autocorrelation times, then plot with gnuplot by

inputting gnuplot H.plt:

The error bar also increases with the autocorrelation.

Press q [Enter] to quit gnuplot.

To get around the bias of autocorrelation, we group the MC steps into

blocks, take the average of the data in the steps of each block, and

then finally average the averages in all the blocks. QMCPACK outputs the

block averages as each line in the scalar.dat file. (For DMC

simulations, in addition to the scalar.dat, QMCPACK outputs the

quantities at each step to the dmc.dat file, which permits

reblocking the data differently from the specification in the input

file.)

Change directories to blocking. Here we look at the time step of the

last dataset in the autocorrelation directory. Verify this by typing

grep timestep H.xml to see that all values are set to 0.001. Now to

see how we will vary the blocking, type grep -A1 blocks H.xml. The

parameter “steps” indicates the number of steps per block, and the

parameter “blocks” gives the number of blocks. For this comparison, the

total number of MC steps (equal to the product of “steps” and “blocks”)

is fixed at 50,000. Now check the effect of blocking on

autocorrelation—type qmca -q e --sac *scalar.dat to see the data and

gnuplot H.plt to visualize the data:

The greatest number of steps per block produces the smallest autocorrelation time. The larger number of blocks over which to average at small step-per-block number masks the corresponding increase in error bar with increasing autocorrelation.

Press q [Enter] to quit gnuplot.

Balancing autocorrelation and acceptance ratio¶

Adjusting the time step value also affects the ratio of accepted steps to

proposed steps. Stepping nearby in configuration space implies that the

probability distribution is similar and thus more likely to result in an

accepted move. Keeping the acceptance ratio high means the algorithm is

efficiently exploring configuration space and not sticking at particular

configurations. Return to the autocorrelation directory. Refresh your

memory on the time steps in this set of simulations by grep timestep

H.xml. Then, type qmca -q ar *scalar.dat to see the acceptance ratio

as it varies with decreasing time step:

H series 0 AcceptRatio = 0.047646 +/- 0.000206

H series 1 AcceptRatio = 0.125361 +/- 0.000308

H series 2 AcceptRatio = 0.328590 +/- 0.000340

H series 3 AcceptRatio = 0.535708 +/- 0.000313

H series 4 AcceptRatio = 0.732537 +/- 0.000234

H series 5 AcceptRatio = 0.903498 +/- 0.000156

H series 6 AcceptRatio = 0.961506 +/- 0.000083

H series 7 AcceptRatio = 0.985499 +/- 0.000051

H series 8 AcceptRatio = 0.996251 +/- 0.000025

H series 9 AcceptRatio = 0.998638 +/- 0.000014

H series 10 AcceptRatio = 0.999515 +/- 0.000009

H series 11 AcceptRatio = 0.999884 +/- 0.000004

H series 12 AcceptRatio = 0.999958 +/- 0.000003

H series 13 AcceptRatio = 0.999986 +/- 0.000002

H series 14 AcceptRatio = 0.999995 +/- 0.000001

H series 15 AcceptRatio = 0.999999 +/- 0.000000

By series 8 (time step = 0.02), the acceptance ratio is in excess of 99%.

Considering the increase in autocorrelation and subsequent increase in error bar as time step decreases, it is important to choose a time step that trades off appropriately between acceptance ratio and autocorrelation. In this example, a time step of 0.02 occupies a spot where the acceptance ratio is high (99.6%) and autocorrelation is not appreciably larger than the minimum value (1.4 vs. 1.0).

Considering variance¶

Besides autocorrelation, the dominant contributor to the error bar is

the variance in the local energy. The variance measures the

fluctuations around the average local energy, and, as the fluctuations

go to zero, the wavefunction reaches an exact eigenstate of the

Hamiltonian. qmca calculates this from the local energy and local energy

squared columns of the scalar.dat.

Type qmca -q v H.s009.scalar.dat to calculate the variance on the

run with time step balancing autocorrelation and acceptance ratio:

H series 9 Variance = 0.513570 +/- 0.010589

Just as the total energy does not tell us much by itself, neither does

the variance. However, comparing the ratio of the variance with the

energy indicates how the magnitude of the fluctuations compares with the

energy itself. Type qmca -q ev H.s009.scalar.dat to calculate the

energy and variance on the run side by side with the ratio:

LocalEnergy Variance ratio

H series 0 -0.454460 +/- 0.000568 0.529496 +/- 0.018445 1.1651

The very high ration of 1.1651 indicates the square of the fluctuations is on average larger than the value itself. In the next section, we will approach ways to improve the variance that subsequent labs will build on.

Reducing statistical error bars¶

Increasing MC sampling¶

Increasing the number of MC samples in a dataset reduces the error bar as the inverse of the square root of the number of samples. There are two ways to increase the number of MC samples in a simulation: (1) running more samples in parallel and (2) increasing the number of blocks (with fixed number of steps per block, this increases the total number of MC steps).

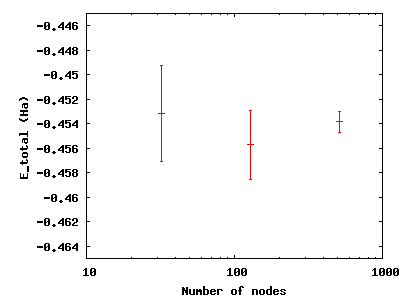

To see the effect of running more samples in parallel, change to the

directory nodes. The series here increases the number of nodes by

factors of four from 32 to 128 to 512. Type qmca -q ev *scalar.dat

and note the change in the error bar on the local energy as the number

of nodes. Visualize this with gnuplot H.plt:

Increasing the number of blocks, unlike running in parallel, increases the total CPU time of the simulation.

Press q [Enter] to quit gnuplot.

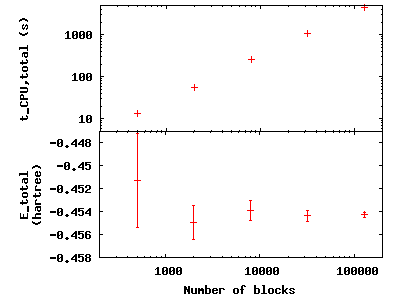

To see the effect of increasing the block number, change to the

directory blocks. To see how we will vary the number of blocks, type

grep -A1 blocks H.xml. The number of steps remains fixed, thus

increasing the total number of samples. Visualize the tradeoff by

inputting gnuplot H.plt:

Press q [Enter] to quit gnuplot.

Improving the basis sets¶

In all of the previous examples, we are using the sum of two Gaussian functions (STO-2G) to approximate what should be a simple decaying exponential for the wavefunction of the ground state of the hydrogen atom. The sum of multiple copies of a function varying each copy’s width and amplitude with coefficients is called a basis set. As we add Gaussians to the basis set, the approximation improves, the variance goes toward zero, and the energy goes to -0.5 Ha. In nearly every other case, the exact function is unknown, and we add basis functions until the total energy does not change within some threshold.

Change to the directory basis and look at the total energy and

variance as we change the wavefunction by typing qmca -q ev H_:

LocalEnergy Variance ratio

H_STO-2G series 0 -0.454460 +/- 0.000568 0.529496 +/- 0.018445 1.1651

H_STO-3G series 0 -0.465386 +/- 0.000502 0.410491 +/- 0.010051 0.8820

H_STO-6G series 0 -0.471332 +/- 0.000491 0.213919 +/- 0.012954 0.4539

H__exact series 0 -0.500000 +/- 0.000000 0.000000 +/- 0.000000 -0.0000

qmca also puts out the ratio of the variance to the local energy in a column to the right of the variance error bar. A typical high-quality value for this ratio is lower than 0.1 or so—none of these few-Gaussian wavefunctions satisfy that rule of thumb.

Use qmca to plot the trace of the local energy, kinetic energy, and potential energy of H__exact. The total energy is constantly -0.5 Ha even though the kinetic and potential energies fluctuate from configuration to configuration.

Adding a Jastrow factor¶

Another route to reducing the variance is the introduction of a Jastrow factor to account for electron-electron correlation (not the statistical autocorrelation of MC steps but the physical avoidance that electrons have of one another). To do this, we will switch to the hydrogen dimer with the exact ground state wavefunction of the atom (STO basis)—this will not be exact for the dimer. The ground state energy of the hydrogen dimer is -1.174 Ha.

Change directories to dimer and put in qmca -q ev *scalar.dat to

see the result of adding a simple, one-parameter Jastrow to the STO

basis for the hydrogen dimer at experimental bond length:

LocalEnergy Variance

H2_STO___no_jastrow series 0 -0.876548 +/- 0.005313 0.473526 +/- 0.014910

H2_STO_with_jastrow series 0 -0.912763 +/- 0.004470 0.279651 +/- 0.016405

The energy reduces by 0.044 +/- 0.006 HA and the variance by 0.19 +/- 0.02. This is still 20% above the ground state energy, and subsequent labs will cover how to improve on this with improved forms of the wavefunction that capture more of the physics.

Scaling to larger numbers of electrons¶

Calculating the efficiency¶

The inverse of the product of CPU time and the variance measures the

efficiency of an MC calculation. Use qmca to calculate efficiency by

typing qmca -q eff *scalar.dat to see the efficiency of these two

H \(_2\) calculations:

H2_STO___no_jastrow series 0 Efficiency = 16698.725453 +/- 0.000000

H2_STO_with_jastrow series 0 Efficiency = 52912.365609 +/- 0.000000

The Jastrow factor increased the efficiency in these calculations by a factor of three, largely through the reduction in variance (check the average block CPU time to verify this claim).

Scaling up¶

To see how MC scales with increasing particle number, change directories

to size. Here are the data from runs of increasing numbers of

electrons for H, H\(_2\), C, CH\(_4\), C\(_2\),

C\(_2\)H\(_4\), (CH\(_4\))\(_2\), and

(C\(_2\)H\(_4\))\(_2\) using the STO-6G basis set

for the orbitals of the Slater determinant. The file names begin with

the number of electrons simulated for those data.

Use qmca -q bc *scalar.dat to see that the CPU time per block

increases with the number of electrons in the simulation; then plot the

total CPU time of the simulation by gnuplot Nelectron_tCPU.plt:

The green pluses represent the CPU time per block at each electron number. The red line is a quadratic fit to those data. For a fixed basis set size, we expect the time to scale quadratically up to 1,000s of electrons, at which point a cubic scaling term may become dominant. Knowing the scaling allows you to roughly project the calculation time for a larger number of electrons.

Press q [Enter] to quit gnuplot.

This is not the whole story, however. The variance of the energy also

increases with a fixed basis set as the number of particles increases at

a faster rate than the energy decreases. To see this, type

qmca -q ev *scalar.dat:

LocalEnergy Variance

01________H series 0 -0.471352 +/- 0.000493 0.213020 +/- 0.012950

02_______H2 series 0 -0.898875 +/- 0.000998 0.545717 +/- 0.009980

06________C series 0 -37.608586 +/- 0.020453 184.322000 +/- 45.481193

10______CH4 series 0 -38.821513 +/- 0.022740 169.797871 +/- 24.765674

12_______C2 series 0 -72.302390 +/- 0.037691 491.416711 +/- 106.090103

16_____C2H4 series 0 -75.488701 +/- 0.042919 404.218115 +/- 60.196642

18___CH4CH4 series 0 -58.459857 +/- 0.039309 498.579645 +/- 92.480126

32_C2H4C2H4 series 0 -91.567283 +/- 0.048392 632.114026 +/- 69.637760

The increase in variance is not uniform, but the general trend is upward with a fixed wavefunction form and basis set. Subsequent labs will address how to improve the wavefunction to keep the variance manageable.